Out of all the bands that were part of the late-’80s/early-‘90s Dischord Records roster, Shudder to Think was one of the least likely to be thrust into the mainstream. But that’s what happened come 1994 when the Washington D.C.-based post-hardcore outfit found their fifth LP, Pony Express Record, released by Epic Records.

Even for a label diverse enough to have Pearl Jam, Gloria Estefan, Michael Jackson, Sepultura, and Oasis under its umbrella, Pony Express Record was an outlier, what with its head-scratching blend of dissonant and experimental math rock, striking vocals, and off-kilter song structures. Buoyed by the MTV 120 Minutes staple “X-French Tee Shirt,” Shudder to Think developed a cult following and stood poised to be one of those bands who, a la Girls Against Boys and Guided by Voices, always had an ardent audience keeping them going.

It didn’t quite work out that way.

Shortly after promotions for Pony Express Record began, frontman Craig Wedren was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Though he beat the disease, the stroke of luck didn’t continue as the next Shudder to Think effort, 1997’s 50,000 B.C., tanked. It was a blessing in disguise, however, as the group shifted into composing soundtracks for indie films like First Love, Last Rites and Velvet Goldmine, before officially calling it a day in 1998.

***

Wedren and guitarist Nathan Larson successfully transitioned into scoring film and television projects – with the former recently soundtracking the hit show Yellowjackets with that dog. singer Anna Waronker – while occasionally revisiting Shudder to Think in a live setting. Still, it came as a surprise this summer when it was announced that the band would be embarking on their first tour in 17 years, as well as making new music for the first time in nearly three decades.

“Every maybe year or two, I would sort of send a bunch of voicemail ideas of guitar riffs and things on the band text thread, and be like, ‘Anybody? Anybody? Bueller?,’ Wedren tells Vanyaland. “And everyone would be like, ‘Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah, it sounds real cool. Maybe we can do something.’ Then, as good things seem to happen, they weirdly happen super-fast. And a week before it happened, I would’ve said, ‘I don’t know, maybe never.’ And then suddenly it was like… it’s just stars aligned.”

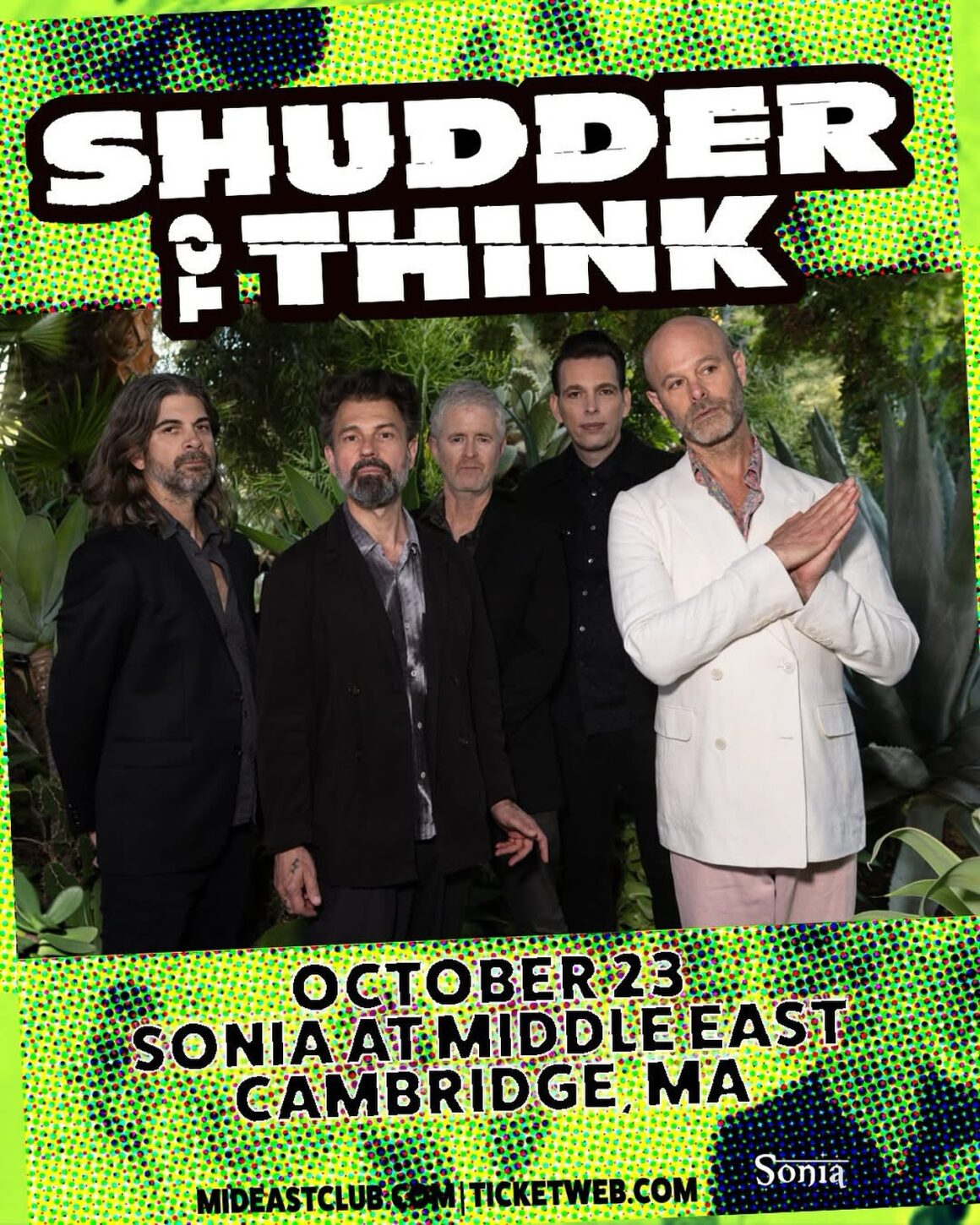

Following a pair of surprise shows in Los Angeles in the spring, Shudder to Think played Riot Fest last month, but officially kicks off the headlining portion of the reunion trek Thursday night (October 23) at The Middle East Downstairs in Cambridge, which was moved to the bigger room after selling out Sonia.

Checking in from his home studio in Los Angeles, Wedren sat down for a Vanyaland 617 Q&A (Six Questions; One Recommendation; Seven Somethings). We talked about the lasting impact of Pony Express Record, the severe health challenges he’s faced over the years, and what it’s like hearing his compositions used in something he’s watching on the screen.

:: SIX QUESTIONS

Michael Christopher: It’s been 17 years since a proper Shudder to Think tour. Why is now the right time?

I think a lot of it had to do with just sort of age and stage. We’re all alive, we all love each other, we’re all very creative on a daily basis. I’ve had pretty serious health issues over the years. Nathan [Larson, guitar] had some weird health stuff, and I think there was just a kind of, let’s call it, “wizened appreciation” for how rare and special what it is that we have and can do together. I think that that combined with the fact that everybody’s kids are, well, actually Clint [Walsh], who’s the new guitar player, he just had a baby a couple of weeks ago with the exception of Clint, everybody’s kids are like teenagers. Everybody’s pretty set.

Is it easier or harder to perform for a more intimate audience when the majority of the room is there for you as opposed to when you’re doing a festival crowd, like Riot Fest last month, where it’s like you kind of have to prove yourself and let people know who you are?

Yeah. It was interesting. Also, just the size and scope, and that kind of diffuse attention that is just the fact of a festival environment. Part of what makes a festival fun is that it’s this kind of ambient carnival. I definitely realized that I was going way bigger with my moves, such as they are; I don’t really have “moves” [laughs], but I was taking up more space at the festival than on the club stage.

But there’s nothing like playing a more intimate show for an audience that’s all there for the same reason. Because between the band and fans, you’re sort of creating this circuit, and especially when it’s something that’s like formative to our DNA, whether you’re a listener and a fan or from the band. It’s like these are old imprintings, whether it’s a specific song or a specific lyric, or a specific memory. I mean, we’re playing new stuff too, because we’re working on a new record – which is remarkably natural and fluid and fits right in with the old stuff – but there’s something more ceremonial, almost doing a smaller, intimate club show than a festival show where you’re trying to win over a new fan.

***

Pony Express Record turned 30 last year. How do you reflect on it now with three decades of perspective?

As with all records, when you make something, it’s a living relationship. If you’d liken it to a child or a relative or whatever, that it’s always changing and mutating and evolving, so it’s not like our relationship to that music sort of stopped when we stopped. It’s like, there would be years where I would listen to it and think it was wonderful in the way that I felt when we made it. And then there are times where I would listen to it and be like, “Dog shit.” And then there are other times I would listen to it and be like, “Well, I love this, but I would change this.” So, it just never stops.

It’s just like any creation. And what’s refreshing about it and makes it much easier to sort of love unconditionally, which is not to say that we ever loved it or any of our records conditionally, it’s there’s always like, “Oh, if we only would’ve done this, or maybe we should have done that, or maybe we shouldn’t have done this,” that there seems to be a new appreciation for it. And also, it’s kind of a new generation of kids coming to it, too. And then also this, I don’t know, it’s sort of like I don’t fuss or fret about it at this point. It’s just like, “Oh, what a beautiful thing we made. This was wonderful.”

When you hear people talking about it or younger kids who are big fans of it, does that give you a sense of validation?

It’s more like a sense of relief. I think when we were younger, we were looking for validation, but a lot of that, I think, has really been smoothed out just with age and other successes and other failures and having kids. It’s like you can keep doing the same thing over and over for nobody or just for a very few people, but that is tough to continue to manufacture inspiration that’s only coming from inside what we’re talking about – being in an intimate concert setting where there’s this sort of circuit between the band and the material and the audience and the band. It all feeds each other. And if there isn’t that, then it’s tough to continue and be excited about it. So that’s the kind of validation. It’s more just a kind of permission, which is sort of embarrassing to say, you would think like, “Oh, fuck ’em, we don’t care. People love it or hate it,” but we do!

Do you think, in a way, that it was ahead of its time?

Maybe. We have a 17-year-old, and he loves Shudder to Think. Some of his friends are, like, fans. He’s our son, so he is like, “Yeah, yeah, yeah, dad, whatever.” He hears it all, but his friends are real fans, and I think that a generation that has only had streaming and internet, really, for their music consumption is way more open to what would have fallen outside of rigid genre categories, which were still very entrenched when we made Pony Express Record. So, I think it’s just easier for them to hear, and they listen to so much, such a wide variety of music, and there’s no stigma attached to, “Well, what is this?” It’s like everything’s weird now.

I was talking to Scott Lucas of Local H recently. And he was telling me about working on the band’s debut record in the studio. They were finishing up mixing, and he got an advance cassette of Pony Express Record, and he immediately got bummed out because he was like, “That’s what I wanted my record to sound like.”

That’s so cool. That makes me feel really good. When that Local H song hit [“Bound for the Floor”], we all gravitated toward it. I remember being in a van together, I don’t know if we were touring Pony Express or maybe 50,000 B.C., but when that song was on the radio, we were like, “Ooh… that.” There’s definitely a kindred thing. That makes sense to me, what you’re saying. That’s cool.

I wanted to ask you about the soundtrack to First Love Last Rites, mainly because I listened to that nonstop when I was in college. I’m guessing that Jesse [Peretz, director] hit you up to do it?

Yeah. Jesse and I were roommates at the time, actually, and he was making his first feature, and he had been directing music videos and had played bass in the Lemonheads for years, speaking of Boston. And he came into my room one time, and he was like, “Hey, check out this short story.” It was based on an Ian McEwan short story. One of the main characters had a collection of oldies 45s, and he didn’t have the budget to license music. And so, he was like, “Would Shudder to Think ever be interested?” And at the time, I was doing some scoring for The State. And so, he knew that I was kind of doing stuff like that, and he knew that Shudder to Think as a band and Nathan, that we were all interested in moving into sort of a film and TV direction.

So, he just basically asked if we wanted to write essentially a collection of 45s for the main character, and that’s what led into it. And for better and for worse, it was really our first foray. So now if somebody asked us to do that, it would sound truly authentic. But what’s cool about that soundtrack is it’s sort of somewhere in between Shudder to Think and actual, authentic oldies. Which we didn’t quite know how to do it yet. It was the first time, and we didn’t have Pro Tools, and we just sort of had a sampler and a guitar and a microphone, so we just sort of made it up. But we were all voracious, omnivorous music nerds. So to be able to get to be like, “Let’s do a Zombies thing. Let’s do a Johnny Cash thing…” that was really thrilling.

***

Some of the work that you’ve done on film and television, Wet Hot American Summer, School of Rock, Role Models, Velvet Goldmine. This might sound like a silly question, but when you watch these things afterward and you hear your music in them, is that similar to seeing yourself in a live performance or…?

Oh, that’s very interesting. No, it’s similar to listening back to a record that you made. It’s more like that sort of dynamic living, breathing, ever-changing relationship where it’s like, “Oh, the bass is too loud,” or, “Oh, that’s the wrong freaking cord,” or, “We needed to mix that.” It’s a constant sort of critical appreciation. And then every once in a while, what we were saying about Pony Express Record or after, it’s almost like after a certain point, it just settles.

Turning a bit more serious, you had battled cancer in the mid-‘90s right after, I guess that was right after Pony Express Record came out. And then in 2018, you had a heart attack. Obviously, there’s the physical toll, but what do these serious life-threatening health scares do to you on an emotional level?

Well, it’s interesting because I think I was 26 when I was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s, and so this would’ve been ‘96 or ‘95 or something like that. And it was like I knew it was going to have radical, permanently life life-altering effects, but I couldn’t really understand what that meant. I hadn’t really experienced anything like that before. And nobody really had died yet. There hadn’t been these seismic mortal things. I didn’t feel like I was going to die, ever, when I had cancer. And my doctor said, they were like, “We know how to cure this.” That said, it was cancer. And so, I didn’t really understand that one.

Then in 2018, I was 48, I guess, something like that. And I had a son, how many years ago is that? Seven years ago? So he was like 10 or 11. That was much more palpably emotional in real time. I had a cardiac event. It was two in the morning. The firemen came, took me downstairs on a stretcher. Our son sleeps right below us, so he, like, came out of his bedroom. So, I was seeing him, seeing me, and.. [at this point Wedren pauses and gets visibly emotional] So, through his eyes – and I was like, some parental thing kicked in where I was just very calmly on a stretcher, headed out, very calmly sort of explained to him, I’m like, “I’m going to be fine. You and mom are going to follow me to the hospital. I’m sure it’s just bad gas, whatever it is.”

So, you went into parent mode…

Total parent mode – briefly. But what I was clocking was, this is interesting. I don’t even know if I thought about this at the time, but my father’s father died of a heart attack on the handball court when he was like 54. So, there’s this whole generational situation too in there, but then it gave me such a will to live that. It was just like, “I’m not going anywhere.”

But then the couple years afterward, there was a real depression/recovery era, which makes perfect sense in retrospect, but I didn’t know quite to expect it where I was waking up every night between 2 and 4 a.m. thinking I was going to die, even though I knew perfectly well I wasn’t. It was just like the intellect versus the sort of lizard nervous system and just a real depression that settled in after that, and a real appreciation for my life and my wife and my family and my kid and my music and and and. Then Nathan actually had his own stuff a few years ago, which I think was a real, I dunno if “light bulb” is quite the word, but just a reminder that we’re all on some sort of weird clock.

***

:: ONE RECOMMENDATION

The movie Eddington. I thought it was the most exciting, refreshing, first movie made by a young artist that was about our sociopolitical moment without being didactic or feeling like I was being preached to. I felt like, “Okay, finally, we’re in a new era where everybody doesn’t feel like they have to be an activist on one side or the other with their political messaging.” You can just express the absurdity of our times and of our humanity, which is always equally absurd, but is in a current particularly ridiculous shape and form, no matter what your beliefs or allegiance is. And I so appreciated that about that movie, and that it just kept taking these hard left turns, which at first I was like, “Oh, no, I’m not going to have anything to hold onto or grab onto.” But the more absurd it got, the more invested I was in it, and I just thought it was a really unique movie.

:: SEVEN OF SOMETHING

Before you moved to Washington, D.C. and became a part of the post-hardcore scene, you grew up in Shaker Heights, Ohio, and you played in a band called The Immoral Minority.

[laughs] That’s right.

Give me seven of the cover songs that you played then, and sort of what your relationship is with them now.

What’s so funny, speaking of Wet Hot, I’ve been playing this band called Middle Age Dad Jam Band with David Wain and Ken Marino. It’s great. It’s great. It’s like comedy and covers basically, and it’s at least half of it is the same set list from when we were 12. It’s like the Jack FM radio. Okay. I’m going to go back to Immoral Minority.

“Just What I Needed” [The Cars] would’ve been one for sure.

“Little Red Corvette” [Prince]

“Ain’t Talkin’ ‘Bout Love” [Van Halen]

“Run to the Hills” by Iron Maiden.

We used to play “Jessie’s Girl” for girls in the neighborhood, because I did a good Rick Springfield imitation. And so they would come over and just want to hear “Jessie’s Girl” because Working Class Dog, the Rick Springfield album, was really popular that year.

“Should I Stay or Should I Go” [The Clash]

“Stray Cat Strut” [The Stray Cats]

Oh wow — you were covering all the bases.

Yeah, yeah. It was just whatever was on MTV…

And you were doing some Journey too?

That was actually in a different cover band I was in. It was called No Tears, and you can picture the symbol: It’s a teardrop with a slash through it. [laughs] I was sort of a hired gun for that. I remember my friend Lee Mars, who played in the band Baby with me and mixed a lot of my scores. He lived around the block from me, and when we were 15 or whatever, he was like, “Listen,” he was always very entrepreneurial, and it was like, “I’m putting together this band, No Tears. This is strictly a moneymaking gig, dude. You’re just hired as the singer.” I’m like, “Okay, okay, man.” [laughs] And so we did “Faithfully.” It was like Journey ballads. What were they? “Faithfully” and one other one.

“Lights?”

No, no, no, not that one. We weren’t that sophisticated. [laughs] “Lights?!?” No, I think it was just “Faithfully.”

SHUDDER TO THINK + ZWEI NULL ZWEI :: Thursday, October 23 at The Middle East Upstairs, 472 Massachusetts Ave. in Cambridge, MA :: 6:30 p.m., all ages, $43.22 :: Event info :: Advance tickets