Before there was The Cult, there was Death Cult, a darker, more gothic iteration of the group that would later become known for hits like “She Sells Sanctuary,” “Fire Woman,” and “Love Removal Machine.” And while a shadowy side existed to the modern version through the years, no matter what musical path they ventured down, it was still surprising when core members Ian Astbury (vocals) and Billy Duffy (guitar) announced in 2023 that they would be doing a very limited number of shows under the Death Cult name.

To put it in context, it would kind of be like if Joy Division were still around and decided to do a handful of shows as Warsaw. Or if Led Zeppelin had one day decided to revisit The New Yardbirds moniker. It was an unexpected manner in which to examine the deepest reaches of the rearview, in this case, 40 years later. But it worked and was so well-received that it’s again being revisited, with a bit of a twist.

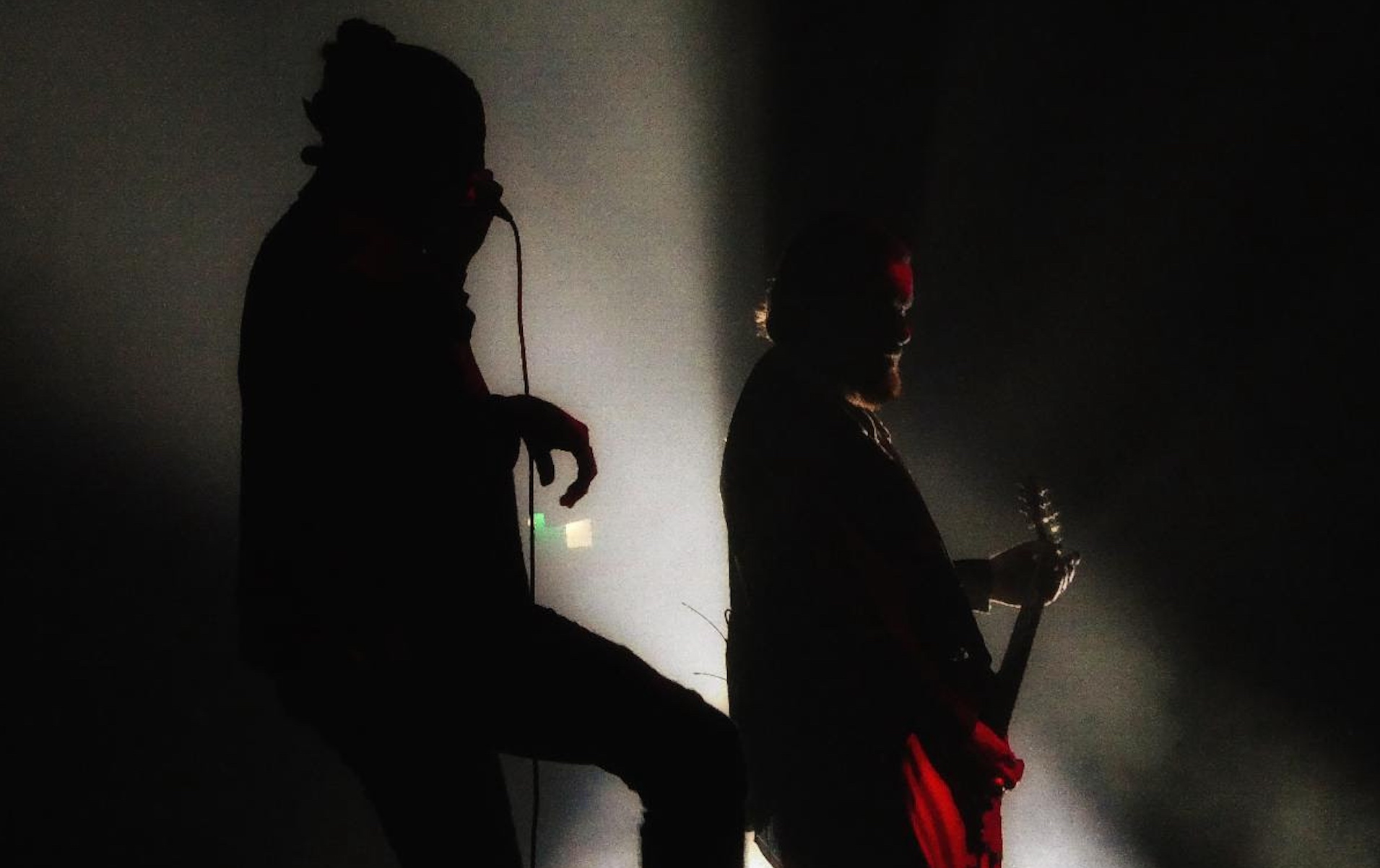

On Saturday night (October 11) at The Orpheum, Death Cult will perform a set, followed by The Cult. The show, which is the second of just 13 North American dates, is a unique opportunity to see Astbury and Duffy approach not just Death Cult singles like “God’s Zoo” and “Brothers Grimm” in a live setting through a present-day lens, but to put in the same box as the songs “Resurrection Joe” and “Spiritwalker,” which were written during the same period but appeared on records under The Cult banner.

“It’s a high-wire act,” Astbury tells Vanyaland. “There’s no safety net. That’s Death Cult.”

Just prior to the tour kick-off this week in Ontario, Astbury sat down for a 617 Q&A (Six Questions; One Recommendation; Seven Somethings) to talk about the decision to bring back Death Cult. The frontman was late to the wide-ranging interview, as he was live-streaming Daughter Minotaur, the musical project of his wife, Aimee Nash, performing at Fashion Week in Paris. Her set was to supplant Belgian designer Ann Demeulemeester’s spring 2026 collection, which is – somewhat unsurprisingly – incredibly goth-inspired. It’s just one more example of what was once an after midnight subculture being dispersed into the mainstream.

“Now it’s the tip of the spear,” Astbury says of goth in the modern day. “And [this] generation is just beginning to wake up to romanticism, poetry, books, tactile experiences.”

Sitting at their home in Los Angeles, it was evident that UK-born Astbury wished he were in Paris cheering on Nash, but Cult things had to be attended to. Rehearsals. Shows. Cross-country travel. But first, there was the Vanyaland 617 Q&A, which is Astbury’s second, making him the first artist in the long-running series who has done it twice. His first was back in 2019 when The Cult were celebrating the 30th anniversary of the Sonic Temple LP. This time around, in addition to the topic of Death Cult, the singer discussed the evolution of his onstage spirituality, reconnecting with producer Rick Rubin, and whether audiences are entitled to a performer’s aura with the purchase of a ticket.

At the conclusion of the interview, Astbury vowed, “We’re going to make it three times.” Let’s get through number two first.

:: SIX QUESTIONS

Michael Christopher: There’s some people who see Death Cult, and then they see the same band come out and do Cult songs. To the uninitiated, what do you say is the difference between the two?

Astbury: The Cult is more like a refined version of Death Cult. The DNA of Death Cult is just raw. It’s the third rail. It’s like getting into a brawl in the street because of the way you’re dressed. You have to get across town, and you’re fully made up on a Saturday night. And we came out of those places where glasses were thrown. There was fights you had to run sometimes to get past the straight soccer hooligans who were going to… I mean, it was an extension of that. And The Cult just followed the natural progression of what was compelling for us at the moment. The transition between Southern Death Cult and The Cult was Death Cult. And that was a pivotal moment for us. So, what it is, is the raw essence of what The Cult evolved into and continues to evolve into.

***

When you first approached Billy with the idea of reviving Death Cult, the Death Cult name, what was his reaction?

I think Billy was very receptive, but he was intrigued. I had to give context, and part of giving context is quite involved. A lot of it is existential. A lot of it is kind of just guttural. I couldn’t define it. Somebody, maybe a cultural savant, could observe and go, “Oh, I can see this, this, this, and this.” But they’re only tactile, superficial elements because music is from your own lived experience. It’s your DNA. Only Ian Curtis can do what Ian Curtis did. Only one person in the world could do that. I can only do me. Billy can only do Billy. So that’s what I was saying to him, is we’re going to go to the lowest common denominator of who we are, what this is. We’re going back to the source because it’s come round, and here we are in this dystopian wilderness, and this is how we responded to our environment when we were coming up.

Was there also a bit of worry that The Cult – at the time – was a hard enough name to push forward? I feel like if you went by Death Cult, you would’ve been more likely to be turned away by labels or asked to change the name.

We were already with an independent label. So no, there was no turning away by label. Are you kidding? CBS Records offered a 100,000 pounds for me when I was 19, in Southern Death Cult. They saw that, and they wanted to throw that kind of money out. It was in the day. [Sex Pistols manager] Malcolm McLaren was saying I was a sexual threat. I mean, it was on from the get go. Could have been called “Egg” – didn’t matter. [laughs] “Give it up for the Black Egg.” It didn’t matter. They wanted it desperately. They wanted the new Pistols. Everyone’s like, “These kids are the new Sex Pistols.” And there was so much pressure on us in Southern Death Cult… the pressure.

It was more about, for me at least, “Does the name get in the way of communicating the songs?” It’s like, serve the song because the songs come from the source. The songs come from lived experience. What is more important, the name of the band or the actual material? And it was all material. It was always about the music. So, we knew that Death Cult was going to be limiting in amplifying, allowing the songs to flow. And it was a hangover from Southern Death Cult. And I was watching the tide turn, and I felt, we don’t want to throw the baby out with the bath water, so let’s just be reductive, lose the Death part.

I want to ask you a bit about your spirituality, because I feel like you’ve gotten more outwardly spiritual, maybe over the past two decades or so onstage, and I’m wondering if that was intentional. It seems like there’s a lot more of your enlightenment coming through when you’re performing live.

Enlightenment. [laughs loudly]

Are you enlightened?

Enlightenment. Wow. I’ve learned, I’ve definitely seen some things and learned some things. I would say there’s an infinite amount of lifetimes to go. “Enlightenment.” Shit. I would say I still know nothing. I’m still learning. I’m a baby. I’m in the kiddie pool. Am I aspiring to have lived experiences and convey that? Yeah, I’m compelled to create, I dunno what… it just is. But in terms of enlightenment, I mean, I get a lot of folks that hit me up, and somebody said something like, “I don’t need psychotherapy. I need to listen to Ian Astbury.” And I was like, “What? Why me?” There’s plenty of savants out there. And some folks, maybe I have spent time around teachings and communities and looked at other cultures and traveled, and you pick some things up along the way. But I believe that anyone can sit and meditate and plug into the source.

But people are seeing that more prominently in you now, which is why you might be getting, “I don’t need enlightenment, I just need Ian Astbury.” Because you put it out on stage. You have these very shamanistic qualities. You lean into it. A lot of others may hold it in, or they’re just out there performing, whereas your performances feel spiritual.

Yeah. It’s probably an extension of my childhood, so perhaps, I dunno. I dunno. I dunno. I mean, all I can say is I do care about it. I care that it comes off in the right way.

I listened recently to your conversation with Rick Rubin on his podcast. What was it like reconnecting with him?

Oh my God, there’s tears. When we saw each other… we were just kids together. I mean, shit. I think when we met Rick, he was still in his NYU dorm room. He was showing us a VHS of Blue Cheer doing “Summertime Blues,” [saying] “You guys should be more like this.” He wasn’t the Rick Rubin that we know today. The savant, the guru, the whisperer, the sun. I’ve always been more of a lunar fem. It’s been said that he follows the sun. In some ways, he has that radiance quality, whereas I’ve followed the moon. I follow shadow.

It was emotional. It was very emotional. I feel we’ve been such a part of each other’s lives at source level. I mean, [The Cult’s Electric] was the first real record he produced. So, it was very emotional connecting with Rick. I hadn’t seen him for quite a long time, but we were very close up until probably the mid-‘90s. And our lives took different directions, and Rick has built an incredible Buddha field that’s helped a lot of individuals. I feel that Rick’s passed on some wisdom of his lived experience, and he’s incredible with artists, and not only artists, but anybody who wants to listen to his vision. I went on my own path.

Was there any talk about maybe you guys doing something together?

I would work with Rick in a heartbeat. I really would. I’d love to work on something with Rick. In fact, you sharing that with me has now got my wheels turning. I’m thinking what could I present to Rick that would entice him so he could be in the same room together? And I think I have something. I don’t know if it’s going to be Cult. I mean, in many ways, Rick and I had a very intimate relationship. He was the perfect producer for that moment. Perfect, perfect person in the room for that moment.

***

You are a big practitioner being present. And in the past, you’ve been very vocal when people in the audience are glued to their phones, taking video endlessly, or famously eating cake while you’re playing a song, a performance where you walked over and took the cake off the guy’s plate and ate it.

Yes. I remember that, actually.

Does it still bother you as much, or do you just kind of look past it now and just say, “Whatever. They’re going to do their thing.”

Whatever happens in the moment happens in the moment. It is distracting at times. But I can be in a room, I’ve played arenas, whatever, where people got the phones out, and I’ve just not been connected… it’s usually when it’s quite obtrusive. Somebody is just behind the camera for the entire show – behind the phone, and I keep walking ’em down like a caged animal. And eventually I’ll just get it, and then I’ll just take the phone or say, “Please put it away. You’re good. You’ve got enough. Now be present. Because you’re messing with the flow. You’re messing with the frequency. We can’t connect. You’re breaking the spell.” That’s a personal choice.

I’ve been at a show and just whipped out – if I saw something real quick – I’m like, bang, hit it done. Back in my pocket. I love the fact that Tobias [Forge] and Ghost, they just got everyone to put their phones [away]. No phones in the building. And, with all respect, there’s a certain ethical component. I mean, yes, you’ve paid for a ticket, but that doesn’t mean you get to leave with the aura as well. Maybe that should be negotiated. If you’re going to come for a spectacle, and you’re going to try and capture the aura in your digital format. I’m on the fence about that. I’d like to hear more from people’s experiences. Going to a show from behind the phone and saying, “How was that for you? Was it fulfilling?”

It’s not really my place to tell people how to conduct themselves as long as they behave themselves. If violence occurs in a room, that stops immediately, we’ll stop playing. The house lights will go up; it’ll be dealt with. It should be a safe environment. But the phone thing is really obtrusive, and it also obstructs other people’s view. Somebody’s got their phone up, and you can’t quite see the performance because there’s a sea of hands. There’s phones up, it can be distracting.

:: ONE RECOMMENDATION

Daughter Minotaur. Go look at the Ann Demeulemeester performance and give you a taste of the dark, futurist, orientalist, romantic, femme, the wave that’s coming. That’s Daughter Minotaur. That’s Aimee. And that’s not because she’s my wife. That’s because she slays. She slayed in front of her peers. It was her and that was magnificent. All day long.

***

:: SEVEN OF SOMETHING

The last time around, you were on the Sonic Temple 30th anniversary tour, and we did a sort of word association with things that had “sonic” in the title. So for this one, I’m going to ask you things that are related to death, to mark the occasion of Death Cult’s return.

“O Death,” the Appalachia folk song.

That’s definitely an individual that’s contemplating the profoundness of being. The gulp of the unfathomable void. How profound and precious life is.

The band Death.

Oh! Now that is a band that – you’re talking about the band from Detroit?

Yes. The proto-punk band.

Oh, stop, please. Yes. All day long. Staggering. I wish they were [still] performing. They did come back for a minute, didn’t they? The documentary brought ’em back. What an incredible hidden diamond. Staggering. I’d love to see more of that Afro punk. Although I don’t wish to diminish or segregate or…to me it’s just raw. It’s their raw truth. And what a fantastic name.

Oh my God. How did nobody have that name?

They did. [laughs]

Death Valley.

Wow…I get so many. Think of B-movies. You think of the Manson Family coming out – they’re in a cave somewhere. Scorpions. Hottest place on earth. Extremities of nature. The extremities of the biodiversity of our planet. How extreme it is – it’s like another planet. It’s like the surface of another planet. It feels like a portal as well, to somewhere. Didn’t Carlos Castaneda..didn’t he get into some shenanigans? When things got weird and he had devotees, and one of the girls disappeared, and Death Valley was mentioned?

Of course, there’s a band called Death Valley Girls, right? Death Valley. It’s the bardos. Maybe the kind of place you would go for a contemplative communion with expanded consciousness. I can imagine a young seeker putting themselves in that environment to be contemplative with the intention of accessing source and the profoundness being. It’s a very, very powerful, powerful, powerful place.

The plague, the Black Death.

Edinburgh. I think it was the city of Edinburgh where they built a city over a city because of the plague. And then I think of Monty Python. “Bring out your dead… it’s not quite dead.” It just turns around is like, “clunk.” It’s so Pythonesque, the concept of us living.

Faces of Death. Do you remember it was the VHS tape that kind of floated around back in the day?

Oh, yes, yes, yes. It was kind of like extreme accidents and… yeah, I remember that. I dunno whether I even watched it. Fascinating. So many ways to go. Hopefully, we wish we all have a favorable death experience. The DMT kicks in just at the right moment. You have a euphoric departure, shall we say.

A song from your bandmate’s former bandmate. “Death of a Disco Dancer” by The Smiths.

I don’t know very much about The Smiths other than “How Soon Is Now?” I remember walking down the street, maybe Walldorf Street, with Billy when [The Smiths] just got together – because Billy introduced Johnny to Morrissey, and obviously it was his first guitar player. So, we’re walking down the street and we’re on Walldorf Street and see Johnny and Morrissey walking down the other side of the street, and Billy goes to say hello, and Morrissey keeps walking, and Johnny came over to say hello. [laughs] Morrissey just kept going. I was like, “Alright, cool.” I didn’t know him. I love Morrissey. I mean, Your Arsenal is my favorite record by Morrissey. I don’t really know the song, but maybe I’ll go listen to it.

Death, as a concept or as an eventuality.

[laughs] That’s the only thing we know is going to happen. You’re guaranteed that one. I went to see Sogyal Rimpoche, who wrote a book called The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, and he’s an enlightened master, Tibetan. I saw him in Kathmandu. He was talking about The Tibetan Book of the Dead, and he goes, “Why is everyone so concerned about death?”

He said, “I guarantee that all of you in this room will do this perfectly. This will be the most perfect thing you do in your entire life.” He said, “But the living part, well, that’s the whole other conversation. So what did we do with the living bit? Don’t worry about the death bit. Concern yourself with how you’re going to conduct yourself with the living.” And that really hit me hard existentially, like, “Oh, right. Oh, okay. Yeah. Pay attention.”

THE CULT + DEATH CULT + THE PATRIARCHY :: Saturday, October 11 at The Orpheum Theatre, 1 Hamilton Place in Boston, MA :: 7 p.m., all ages, $44 to $193 :: Event info :: Advance tickets