The sidemen in rock and roll are often an under-appreciated lot, guns for hire that step into a situation at any given time, be it in the studio or on the stage for a marquee performer needing that extra juice, a musical shot in the arm to bring things alive. Usually nameless and faceless, there are the exceptions. Take Earl Slick, for example. The Brooklyn guitarist hooked up with David Bowie in the mid-’70s during the Diamond Dogs tour and quickly became a favorite of the fans and, more importantly, the man in charge, subsequently working on the landmark efforts Young Americans and Station to Station.

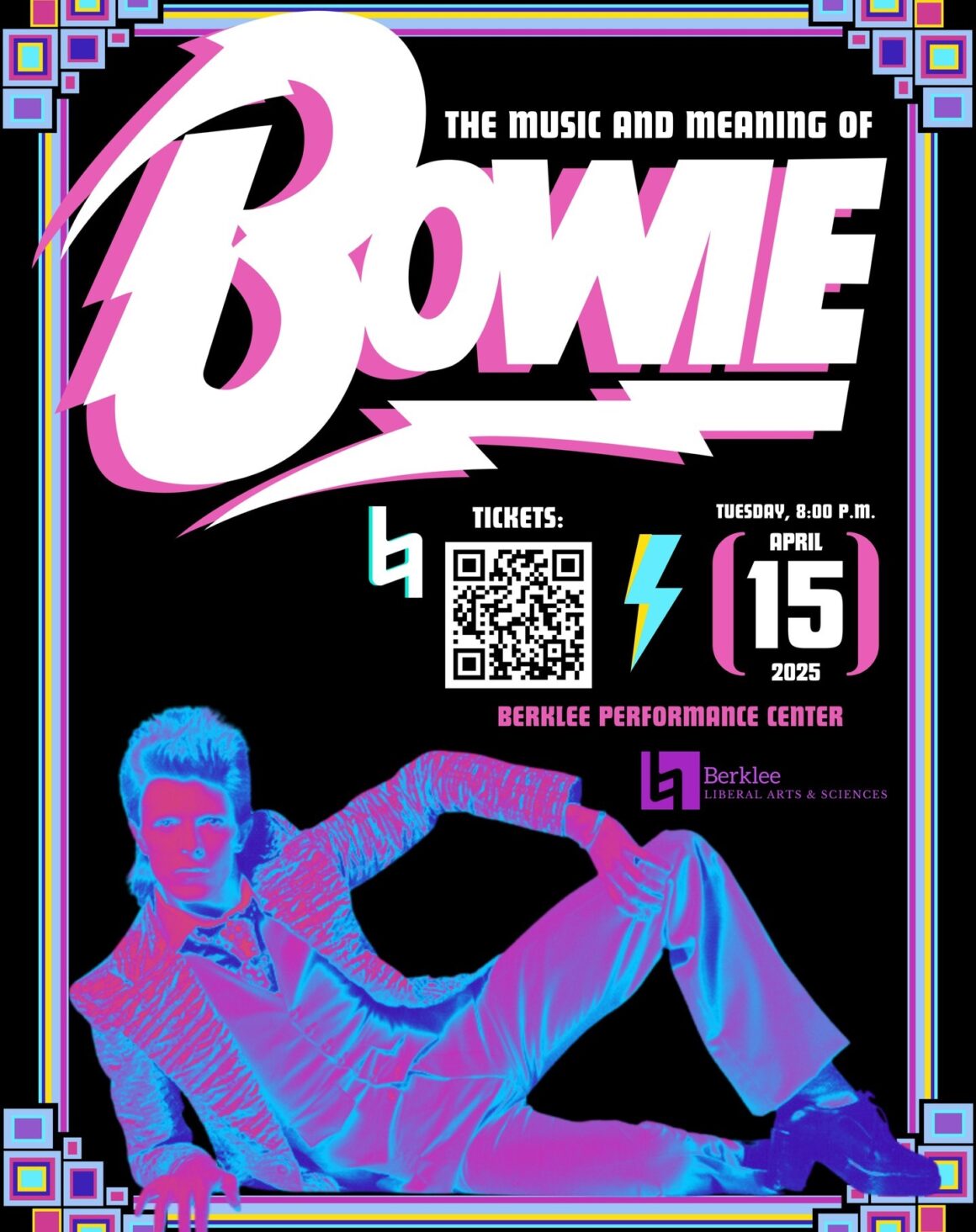

The long and fruitful partnership opened the doors to collaborations with everyone from John Lennon to Joey McIntyre from New Kids on the Block to Whitesnake’s David Coverdale to Robert Smith of The Cure. Those are just a few of the reasons Berklee’s Liberal Arts and Sciences Department enlisted Slick as the featured performer at Music and Meaning in the Works of David Bowie, a concert taking place Tuesday night (April 15) at the Berklee Performance Center in Boston. Prior to the gig, he’ll meet with students from a course on Bowie taught by Professor Gretchen Shae and also lead a separate master class for guitar students at the college.

“When [Berklee] called me, I thought, ‘What the hell can I teach these guys? They know more than I do!’” Slick tells Vanyaland. “And then, wait a minute. There’s the other part that they don’t know.”

That “other part” is the intangible that comes with being a captivating artist, an enduring swagger that Slick has in abundance. He also knows how vital inter-band dynamics can be, how to deal with strong personalities who, by nature, want to run the show.

Ahead of his arrival at Berklee, Vanyaland sat down with the guitarist for a 617 Q&A (Six Questions; One Recommendation; Seven Somethings). Despite the recent losses of two close colleagues in Blondie’s Clem Burke and New York Dolls frontman David Johansen – the latter who he calls “my best friend in the world” – Slick was animated and engaging, looking every bit the rock and roll star he’s been since first strapping on the six string. The 72-year-old talked his time alongside Bowie, what he hopes he can teach students, and some deep-cut musical associations from the past.

:: SIX QUESTIONS

Michael Christopher: Over the years, you’ve done so much work with students of music, from School Rock to the upcoming Berklee event. Why is it so important for you to impart your wisdom on the future generation of musicians?

Earl Slick: I think it’s kind of important that [students] realize that when they get out of there, they may know the notes, they may know all the chords, and they may know all the theory, but… you can play the notes, but can you make the music? Which is something that may sound like a stupid statement, but it’s really not, because I’ve sat in with guys that technically would blow me out of the water. I feel nothing when they play. And the problem with that, with the younger guys, is they’re playing either in their bedroom or interacting with a guitar guy, a teacher online, and getting in a room together… you ain’t a rock and roll band unless you play live. That’s where this comes from, man.

When you work with students, does it keep you young in a way?

You know what? Just playing my guitar does that. But what I do like to get out of it, what I really like, what it does for me, is as far as keeping me young, it helps me digest their process, their thought process. You know what I mean? And you can spot the ones that have the intangible, you could spot ’em a mile away. You really can. And if it wasn’t for the intangible, I couldn’t make a living at this. No way. If I think about it, let’s say go back to 1974 when David asked me to join his band, he had his choice of anybody on the planet, and I did an audition – I’m the only one that auditioned – and I got the gig, and it was the intangible part.

You could have someone that comes in, and somebody might say, and — I’m not saying this is you — but “Oh, that guy’s really sloppy technically, but they have the swagger.” They have that thing that you can’t take your eyes off of them when they’re on the stage. I don’t know how much of that you can teach to somebody, but what do you think that students will get out of something like this, what you’re doing at Berklee?

I think what I could bring to the table is that there’s a lot more to this than what you learned here. Now, you learned great shit here because it’s the best place to go in this country, but what you can’t teach them is the other thing. But what you can do is you can lead them to the process. They go, “Well, how do I do that? How do you put a band together?” “Well, you do this, this, and this.” And then I can share with them how I did it and how I still do it.

It’s still important that the interaction between them and them dedicating themselves to the band. Or some of ’em are going to come out of there not knowing how they want to apply it. Some guys may want to be a solo artist. Some guys might want to be in a band. Some guys might want to be a session player. And the only way to find that out is once they get out and start playing with people. Follow your comfort zone, man, because that’s probably where you’re going to be your best.

***

I want to get into your history a little bit. One of the things about your playing, on [Bowie’s] Station to Station, for instance, has always stood out to me because at times you’re playing as moody, it’s funky, it’s bluesy, it’s kind of all over the place, but it still coalesces to create this unified work on the album. How intentional was that, or did you just go with the feel?

It was intentional on David’s part. First of all, a lot of it happened naturally as far as the band goes, because [guitarist] Carlos Alomar and me are absolutely, totally left and right. Matter of fact, I think on the mix, I’m on the left and he’s on the right. You can tell us a mile apart. There’s no conflict of guitar in there, all because what me and Carlos were both doing was what came naturally to us. And a lot of that was done with myself – and David after the basic tracks – spending a lot of hours just playing through until something hit us, just two of us in a room. And David pushed me out of my comfort zone, seriously pushed me out of my comfort zone on that record. But obviously, I had a natural tendency towards it, or it never would’ve happened. We wouldn’t have pulled it off. So, he had a really good instinct about that stuff. So intentional from the band? No. We kind of mixed up a bit of funk and rock, and listening to it. Now, the guitar work I did sounds normal to me, but apparently, back then, it was a little out of the box.

I’m originally from Philadelphia, and one of the biggest badges of honor for music fans and music nerds from the region is that Young Americans was recorded in part at Sigma Sound. Not only was it recorded there, but it was sort of a milestone for David in a few different ways. One, he rarely worked outside of the UK at that point on new material, and it was also another transitional moment for him, out of the Diamond Dogs era into the blue-eyed soul. What do you recall most about that time?

It’s a funny thing about that record, and I’ll give credit where credit’s due on the guitar end, that was really carried by Carlos, just like Station to Station was carried by me. So, I instinctively knew what to do was play for the song, play for the song. The bits I did on that record, they had nothing to do with anything other than this is what this song needs. And in the case of that record, it really needed a lot more Carlos, and on Station, it needed a lot more me, and your instincts kick in then. Me and Carlos never sat and discussed, “You do this, and I do that.” As soon as we started playing the tune, that just happened.

So, there wasn’t a lot of stepping on each other’s toes.

None.

It’s more just kind of, not that you know your lane, but that you’re maybe respectful of what each other is doing on the record?

It’s an instinct thing. It also is a testament to David Bowie’s genius because he picked people for specific reasons. He knew that he needed Carlos’s funky thing, and Carlos’ funk really comes from a pop funk area. He did stuff with the O’Jays, and he’s done stuff with James Brown and all that stuff. So, it was obvious who was in this lane and who was in that lane.

When you would see David go through those changes – no pun intended – but sort of the transitions, was there ever any part of you thinking, “Wow, this is really different than what’s happening on Diamond Dogs or what we’re touring right now. This might not be the best path to go down musically…” or did you just always have complete faith in whatever he did?

I had faith in what he did because he was going to do what the fuck he was going to do [laughs]. So, I had to figure out, “Okay, what do I do?” And that’s something that these guys [music students] got to learn, too. I mean, what I’m best at is being a sideman. Even if you’re in a band, to me, the job is that you get hired by somebody, like David Bowie, and your job is really – especially live – to make sure that the band is very varied together, because our job is to make sure that he’s comfortable enough to sing to what we’re doing. You find that little niche in there because that’s your job. You’re the glue that holds it all together so he can do his job, so he’s not looking over his shoulder every five minutes going, “What the fuck are these guys doing?”

Recording Young Americans, there were the “Sigma Kids”.

Oh, I know them. And they’re all 70 now!

Local legends. Had you ever experienced something like that before or since, where these kids were just living outside the studio while the recording session was happening, and eventually invited to come in?

No, not like that. And it’s funny, because I was surprised at the time that they actually let them come in. And with David being the way he was, I mean, when we did Station to Station, I think during the whole recording, maybe two or three people showed up. Keith Moon came to a rehearsal, so that rehearsal was over as soon as he walked in the room, it was fun, but it was over. Iggy [Pop] stopped by, and he walked in the studio, and there was a tray with some drinks and food on it. He walked in the studio, walked right into it, head over heels, and landed on his back, and he introduced himself. That was that. The rest of Station, nobody came in. None of our records, actually, it wasn’t party time.

So, it did surprise me when he let these kids in there; they camped out. Even [Bruce] Springsteen was camped out one night. We recorded two of his songs on that record. One of ’em is me, and the other one is Ronnie Wood. [Note: Both were eventually scrapped] So that was definitely a not usual situation for sure.

***

Shifting gears, you were in Little Caesar for a bit. Unfortunately, it was at a period when that type of music was sort of on the way out, and the focus was on grunge. There’s a lot of fans out there who think that had it been a different time, maybe even just a few years earlier, that band would’ve broken big.

Absolutely. Also, got to understand something, man, when you’re in a band, you just married four or five guys, period. And you have to learn how to maneuver all the stuff that comes up. With Caesar, actually, the guys were pretty cool, all that stuff. But there were problems inside the band. There was relationship problems with management – or lack thereof. I think had there been better management, that band could have happened because they did have a pretty good run with the Aretha song [“Chain of Fools”]. And they did a great job of it. It didn’t sound like some crass heavy metal shit. It was really good.

All the elements were there for Little Caesar. I think part of it, you’re right, is that timing where all of a sudden Seattle took over the world and people were, I think the whole hairband thing, it got old pretty quick. But as you think about that, [grunge] didn’t have that long of a run. It really didn’t. But credibility-wise, as far as time went, it’s actually held its respect, or it’s still held onto its integrity, where if you look at a lot of [hair metal] bands, I’ll name none of them, if it wasn’t for MTV and tits, they wouldn’t have sold two records.

Earlier, you mentioned David and Clem, and of course, along with David Bowie in 2016, you’ve seen a lot of your contemporaries and friends pass in recent years. Does that make you start to think about your own mortality when you lose people that close?

It really didn’t until the pandemic hit. I never thought about that. Even when David died – Bowie – I wasn’t thinking about that. But it’s funny because just a year into the pandemic, I got diagnosed with Lyme disease. I was out of it for two years. I mean, it didn’t work at all. And that’s what started me thinking about it. And now my friends…it’s not been a good year. Two of ’em in six weeks, especially Johansen, I loved David. He was probably one of my closest friends ever. And it made me think of my mortality. Not so much that I’m going to die, we all know that. But it was like, “Okay, what are you going to do with what time you got left? What is it going to be tomorrow, next year, 20 years?” You don’t get to know that.

:: ONE RECOMMENDATION

Being open to influences. I am affected by art and fashion for sure. I also think that if you’re going to be, say, in a band or you’re going to be somebody that plays live, it’s something that you kind of need to pay attention to. And I do draw from things. I do draw from art, and I even draw from out-of-the-box stuff. So yeah, it’s all, to me, if you talk “out of the box,” I think that music and fashion and all of that are so intertwined, especially for a live band. And one thing inspires the other. Even what I wear in any particular situation it happens to just be where my head is at the time. So, I just do whatever that is.

***

:: SEVEN OF SOMETHING

You’ve worked with quite a few artists throughout your career. I’m going to give you seven of them, and want you to tell me what comes to mind.

David Coverdale.

Rockstar. When we did the writing on that record, it was more rootsy-sounding before we recorded it. And as we did the recording, David was falling back into that comfort zone a little bit. It definitely wasn’t heavy duty like Whitesnake, but I think the whole idea of that record was, it was going to be a really more rootsy record. But when we started recording, as a lot of artists will do, they start to go, maybe this is just too far away from what they know. And so some of it got a little bit too polished for me. The end result was definitely more polished than I expected it to be.

John Lennon.

Oh my God. Anomaly. And the fact that he was in a band that turned the world upside down, playing pop music, even though they did do [Sgt.] Pepper and stuff like that. But when he went on his own, he did the opposite of what McCartney did. He got introspective with his songwriting, got very personal with it, political with it. He was an anomaly like that. He came out of a band that you would think he would try to continue that pop music, and he did a few, but if you listen to those records, a lot of them were pretty dark.

[laughs] It was a strange experience. She was quite the strange character. I mean, Jack Ponti was the producer, and he had to keep it all glued together, or it would have exploded.

I feel like she’s one of those people who is always on. She’s always “Doro.“

She was exactly the same having dinner as she was when we were working. It was just, yeah, it was 24/7.

Joey McIntyre.

That’s funny. Joey… Mark Plati was doing the record – that’s why I ended up doing that thing. And Joey was a cool guy. He was a good-looking dude. He had a lot of charisma. The girls loved him and all that, and the music was what it was. And, somehow, I managed to fit in on a couple of tunes.

Robert Smith.

Ah, Robert Smith, man. True artist. Absolutely true artist.

Mick Jagger.

Mick Jagger is a bit of a character because there’s that side of Mick that we see as the performer that he’s so great at, but on the other hand… I only met Mick a few times. One of ’em was, is when I got called to do the guitars on the thing he did with David, “Dancing in the Streets.” And he was very, very businesslike. Nice, but very businesslike.

Yoko Ono.

Another anomaly. She is a true artist, and she did not get a fair shake. She basically married into a shit storm – she did. But when we did Double Fantasy, I was quite surprised by some of the stuff she was writing, and – talk about out of the box. I mean, she was already in the B-52’s area back then, and very, very distinct at what she did. And then I did her solo record after John died, and I could see the artistry in what she was doing. She could write songs. She really could.

MUSIC AND MEANING IN THE WORKS OF DAVID BOWIE :: Tuesday, April 15 at Berklee Performance Center, 136 Massachusetts Ave. in Boston, MA :: 8 p.m., all ages, $12 in advance and $17 day of show; Berklee students free in advance and $5 day of show :: Event info :: Advance tickets