When Shane MacGowan passed in 2023, it seemed as if he was finally in a good place after a life at the other end of the spectrum. The revered frontman for the Celtic punk outfit The Pogues often had his talents overshadowed by drunken antics, with his hard partying ways and drug abuse the stuff of legend. During one 2007 show at Boston’s Orpheum Theatre, sloshed and unsteady on his feet, he took a nasty tumble and destroyed the ligaments in his knee. Yet – and maybe it was the alcohol numbing the pain – he limped out for two encores and did the remaining dates from a wheelchair.

Underneath all that, though, was a sensitive poet, admired greatly by such Irish notables as U2’s Bono and the late Sinéad O’Connor. Unfortunately, when MacGowan died, it looked like that was it for The Pogues, who had gone through their ups and downs since the singer founded the group along with vocalist/tin whistle player Spider Stacy and multi-instrumentalist Jem Finer in the early ‘80s. “Ups and downs” might be putting it politely; at one point, MacGowan was kicked out, with Joe Strummer from The Clash briefly recruited as his replacement.

Having been on indefinite hiatus since 2014, with the nail in the proverbial coffin being MacGowan’s death, it was quite the surprise when the surviving members of The Pogues reconvened in the spring of 2024 in London with a handful of guest vocalists to perform the band’s debut, Red Roses for Me, in its entirety for the record’s 40th anniversary. It was so well-received that Stacy, now viewed as the de facto leader of the unit, commiserated with the others and decided to move forward in a move that feels less like a cash grab and more a celebration of songs that people want to hear again in a live setting.

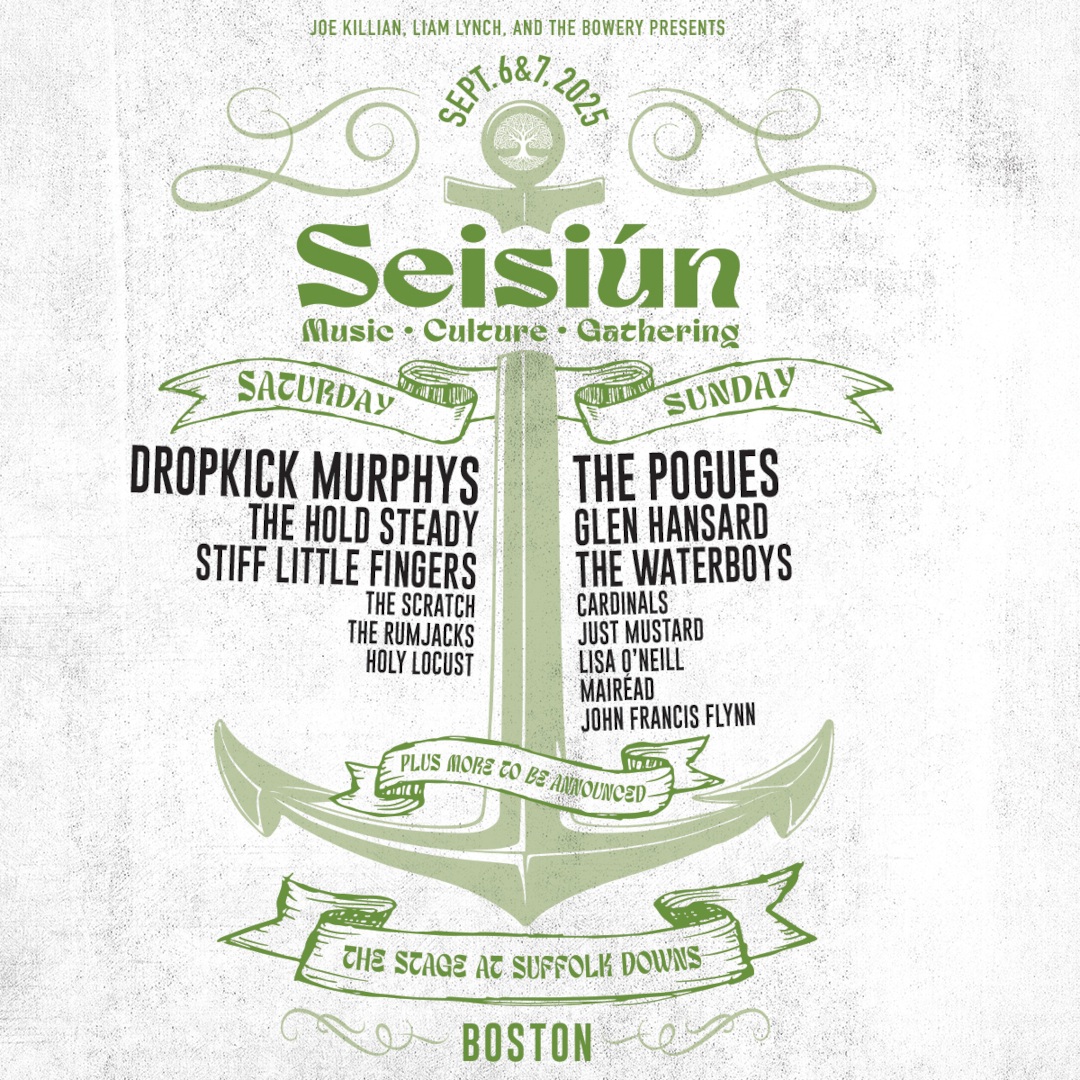

This year marks the 40th of The Pogues’ landmark sophomore effort, Rum Sodomy & the Lash, which they’ll be playing in full across nine dates in what will be the first shows in North America in 13 years. Included is a headlining slot on the second day of the inaugural Seisiún, a celebration of Irish music, arts, and culture taking place this weekend at Boston’s The Stage at Suffolk Downs. The Saturday slate (September 6) sees The Dropkick Murphys, The Hold Steady, Stiff Little Fingers, and more on the bill; with Sunday (September 7) offering The Frames’ frontman Glen Hansard, The Waterboys, and others going on before The Pogues.

Vanyaland sat down with Stacy twice over the summer to discuss the return of The Pogues, once at the residence of the Consul General of Ireland in Boston, and later via Zoom while he was back home in England. The conversations touched on his memories of MacGowan, the decision to resurrect The Pogues, and what the support vocalists, including Iona Zajac, Lisa O’Neill, and Nadine Shah, will bring to the current lineup.

Michael Christopher: Most see the Pogues as an Irish band, even though they got started in England. Was it ever weird for you as a Londoner to be so closely associated with Ireland?

Spider Stacy: Well, actually, no. I think and always thought that the Pogues are primarily a London band. Our initial core audience – I don’t even know if that’s quite the right term, but yeah – let’s say core audience were definitely, I think London-Irish kids, sort of kids of the children of the diaspora, and also, especially at that time in the ‘80s, and there always have been a lot of people who living in London who had come there directly from Ireland, young people. But also, I mean, London has such a huge… There are so many people with Irish blood in London. Their connections to Ireland might go back generations. It might be 200 years that their family’s been over here, but it runs deep.

To answer your question, I mean, there was never any kind of paradox or conflict or anything there, because as I say, we were first and foremost really a London band, and I think we could only have been a London band, even of terms of being a London-Irish band, if you want to call it that, which I guess is a valid thing to call us. But we could only have been a London-Irish band. I don’t think the Pogues would’ve been the Pogues had they come from any other city, whether inside or outside of Ireland… And I think London, if you’re looking at, say, Shane’s lyrics, London was a very, very important city for Shane. London was where the world opened up to him in a sense – but always informed by Ireland, of course, and with a sort of exile’s viewpoint as well.

Talking about Shane’s lyrics, it kind of brings me to this point, which is that being overtly political was never really The Pogues’ thing, although there was a strong undertone, especially if you examine the lyrics closely.

I think it’s implicit. I think there’s an implicit standing on the side, if you like, of the downtrodden of the have-nots, the dispossessed, the people who are forced to migrate, not the people who choose, necessarily, [like], “I think that sounds fun, we’ll go and live over there.” You know what I mean? The people who have to, because of whatever reason, be it famine or just the lack of work or anything like that.

Also, given the context of where we came from, London in the ‘80s, for us to be doing what we were doing, it was very, very clear what side of the coin we were. Essentially, you’d have to be kind of dumb to associate The Pogues in any way with any kind of right-wing politics. Let’s not mince words here.

Did you want the politics to be more tempered within the band, or did you not really have a care one way or the other?

That was never ever an issue. We were never about, as you say, we weren’t overtly a political band. The Birmingham Six happened. That was something that kind of demanded a response, just the sort of thing of these guys being locked up for life for something that they – or being sentenced to life terms for something that they clearly hadn’t done that everyone knew they hadn’t done, but the people who had done it were saying, “These guys, it wasn’t them. It was us.”

***

And given the nature of the band, I’m not going to deny the Irish dimension – that would be facile and stupid. It was always about more than just dealing with sort of political subjects, political issues. If you say, I think you’re probably getting at the whole, if you like, having a point of view on The Troubles or the Irish. I think, again, it was extremely clear to anybody with half a brain where we stood on that, but there was no need for us to add our voices to that.

Speaking of voices, and on a much lighter topic, not a lot of people know this, but you and Shane were originally going to share vocal duties when you started The Pogues. How come that didn’t play out?

Oh, I wasn’t up for it. I really wasn’t up for it at that point. Nah. I didn’t have the confidence. I didn’t know how to do it. I think my voice has got better over the – I know my voice has got better over the years, and I feel much more comfortable now about doing it, but at the time, no, I wasn’t ready for it. Interestingly, now we’ve got this plethora of singers, we’ve got this, we’re absolutely spoiled for choice.

Tell me a little about the singers you have on board now.

The people that we’ve got…we’ve got Nadine Shah, who, I dunno if you’re aware of Nadine –

She’s amazing. I love her so much.

Yes, yes, yes. What I hadn’t taken into account, because I don’t actually think I’ve ever worked with one before, is that Nadine is a trained singer. She’s actually properly trained. So, when she did the soundcheck, she was, she’s just putting a little bit of pressure on the accelerator, really kind of first gear. She came out to do the song [live], and it was just like, “What the fuck?” It was extraordinary.

There’s a woman called Iona Zajac who’s actually beginning to get her name for herself now in Britain, and she’s fantastic. She’s got a beautiful voice. She plays the harp. We’ve got this, I think, this really extraordinarily striking visual setup. We have a harp, a proper Celtic harp, on the stage.

[And] when you listen to someone like Lisa O’Neill and the words that she writes, and you’re just like, “My God, where is this woman coming from?” She joined us for the British tour, the Rum Sodomy & the Lash tour. And, honestly, just being on the same stage as her is just like, extraordinary. And to hear her, the way that she sings a song like “Rainy Night in Soho,” she’s an extraordinary singer and an extraordinary interpreter of songs in the way that Shane was, but obviously very much in her own way.

***

When Nirvana started doing one-offs at either the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, or they would do a gig for charity, they were using female singers. Joan Jett and St. Vincent, which a lot of people didn’t really think about how Kurt Cobain’s lyrics would sort of lend themselves to a female voice.

That makes complete sense. I mean, one of the things always of the things I always really liked about Kurt Cobain was something he said, I guess he was kind of looking back at when Nirvana was starting, and he’d said that he’d wanted to create a space where women felt safe because in punk shows and whatever, it sounds like they were pretty hairy places that you wouldn’t necessarily, they didn’t sound like it was a whole lot of fun, really, for women especially. And that always struck a chord with me because I’ve always felt that you lose so much when you’re bands whose audience is like 90 percent male, whatever, which a lot of bands, that is the case, and… I dunno, I think you need women there. You need women on the stage. You need the sound of women’s voices, and obviously, they would lend themselves perfectly to Nirvana’s songs.

And the same with Shane’s is what I’m getting at. Are you surprised at how well his lyrics work for female singers?

No. No. I’m not remotely surprised. They’re great lyrics for one thing. So, I mean, it’s down to the singer, I guess. But no, I’m not in the least bit surprised. I think it’s always actually very effective when you have a song that maybe you would associate with a man singing it, being sung by a woman. And it actually works the other way around as well. I mean, it’s very common. It’s extremely common in folk music.

What are you calling this iteration of the Pogues? Is it a resurrection, a reunion, a celebration?

Well, initially, all it was really was a celebration – or an anniversary – of the first album. [It was] the 40th anniversary of the first album of Red Roses for Me last year. I got an email from Tom Coll from Fontaines D.C. and a friend of his who’s a kind of small promoter in London, a guy called Campbell Baum, who kind of does this sort of thing. And they were just doing a weekend of Irish music at a folk club in East London, and they said, would I like to curate the Friday night to celebrate 40 years of Red Roses for Me. And I thought, “Okay, yeah,” without any thought really of getting any other Pogues involved, because I knew obviously that kind of thing wouldn’t have much budget. And that’s kind of how it started, because it sold out as soon as we announced it, it just sold out with a huge waiting list.

So, we moved it to a bigger venue, and Tom Coll was able to sort out a bigger budget, sort of sponsorship, and stuff. It helps having somebody who’s in a really happening current band and that kind of situation. [laughs] And so then I was able to go to Jem [Finer] and say, “Look, we’re doing this, do you fancy sort coming and playing?” And I was able to get James Fearnly over from Los Angeles… I just thought, “Well, we’ve got these guests, musicians like pipers and banjo players and whatnot.” And I thought, “We need singers, we need singers,” and I thought I wanted to have a strong female representation.

And it just naturally fell under The Pogues’ banner.

I mean, we did Red Roses for Me and then Rum Sodomy & the Lash, we’re going to be bringing Rum Sodomy & the Lash, plus loads of other songs as well, to the States. I think…we’re not going to stop here. I think that’s pretty much a given. And whilst on the one hand I like the idea of, “Okay, we do 40 years or whatever, 39 years perhaps [the 1988 LP] If I Should Fall from Grace [with God].” But at the same time, there’s a case to be made out for just like, well, we’ve kind of established this now as a thing. Do we need to keep pinning it on sort of a particular album? Should we just maybe at some point just start doing, if you like, a greatest hits set – I suppose.

So, yeah, it’s all a bit…there was all kind of discussions about what we were going to call ourselves, because there was a certain amount of reluctance I think, amongst us just to say, “Yeah, we’re The Pogues,” just like that. But at the same time, [laughs] that’s what everyone else is calling it. And I think that’s what people are seeing. I guess – yes, of course, of course it’s The Pogues. If you like a Pogues’ big band, I guess, or Pogues Kaley Orchestra. I quite like “The Pogues Big Band” sound.

What about the people who say, “This is blasphemy. You can’t call it The Pogues without Shane.”

It’s a funny thing, because of course there has been – like on The Pogues Facebook – that’s the worst place for it, where you get people saying, “If it’s not Shane, then it’s not The Pogues.” The thing is, anytime I’ve seen someone who’s said that, the replies underneath have basically been like, “Were you there? Did you see the shows? Because if you had, you wouldn’t be saying this. I don’t want to sound like a wanker again, but I mean, honestly, you’re going to tell me that Shane wasn’t at any of those gigs? Come on. He was watching all of them.

***

What are some of your favorite memories after reuniting in the early 2000s? I mean, I know there were some not-so-great memories. I was at the gig here when Shane really messed up his leg…

Actually, he did his ligaments in in his knee. I’m glad you asked that because, I’ll be honest, there were times during the reunions where Shane wasn’t all he could have been. He was just tired, maybe too much to drink, whatever, whatever, whatever. And I guess there were times when we’d have to be keeping an eye and making sure that, “Okay, is he still singing the same song that we’re playing? Alright, that’s good.” That sort of thing. [laughs] We were kind of used to that sort of thing happening. Shane had always had a – maybe not so much in the early days – but as time wore on, always had a slight tendency, sort of, to drift. But it was also actually quite easy just to, “No, actually, there you go,” [mimics guiding Shane back].

After that show, where he tripped over a bass cable – that really wasn’t his fault. The next night he had Reiki healing, which is something I barely even really know what it is, I think sometimes I don’t even touch you. They just run their hands… And it was extraordinary. He couldn’t sort of stand for a whole gig, but we got a wheelchair for him, and he sat on stage in this wheelchair, we had barely any lights, and he was a big guy at that point, and he was wearing all that mad jewelry that he used to wear and shades, and he really looked like the fucking prince of darkness. And he sang absolutely fucking brilliantly. I think. I guess Reiki healing really does work because it seemed like he’d got the strength from somewhere that wasn’t any kind of in any way sort of chemically induced or anything like that. I mean, I was standing alongside him, and I was mesmerized by this presence, so that was great.

I think a lot of Irish music in general is seen maybe more in America than anywhere else as drinking songs and fighting songs, and that’s what a lot of it’s about. Did it ever bother you to see people celebrating the partying aspect more than the musical aspect? Or, people might be like, “Oh, it was such a great show because Shane was so wasted –”

That I hated. That I really, really hated. But the thing about people enjoying the partying aspect more than listening to the songs, if we were to complain about that, then we’d only have ourselves to blame because we wanted that, we brought that. We wanted people to basically get fucked up and have a really good time. But it… it’s how you’re meant to dance it. We knew with our audiences also, of course, they’d listen to the songs.

The stuff with people, “Yeah, Shane was really messed up, and it was great,” that I’ve no time for, that’s just voyeurism. But you’ll hear people saying that or you’d sort of see people saying that, and it’s like a lot of people would be like, it’s a shame Shane is so fucked up. It comes with the territory.

Boston is one of those cities that has always been a big supporter, not just of the Pogues, but of Irish music in general. What do you attribute that to?

Well, I mean, Boston is famously one of the real Irish American [cities]; it’s a city that is so strongly identified in the eyes of the world, really, if you think of Boston and if you know anything at all about the city, you think about the Irish because they’re such a very visible and prominent part of the city. It’s such an important part of the city.

So even for us debased barbaric Saxons, even we were aware of this and the fact that the basketball team is called the Boston Celtics – that’s a giveaway. But it’s clearly, yes, this is a very Irish city. What’s interesting, of course, about that is I can hear New York and Chicago both yelling, “What about us?” Guys, you’re just going to have to discuss this amongst yourselves. I’m sure you’ll come to a completely amicable [solution]…and that’ll all be settled and… yeah.

Now that you’ve had a good amount of time, amount of distance, how do you look back on the period when Joe Strummer was fronting the band?

I mean, it was just a blast, really, from my point of view. I mean, I was a huge Clash fan. When Shane left, or we had to get rid of him. We were kind of a bit of an impasse, and the idea of actually using Joe just seemed… inspired – because it really, really worked. Yeah, it was probably the most fun thing about the post-Shane Pogues. Maybe the only fun thing, really, if I’m going to be honest. [laughs]

SEÍSUN FEATURING. THE POGUES + THE DROPKICK MURPHYS + THE HOLD STEADY + STIFF LITTLE FINGERS + GLEN HANSARD, AND MORE :: Saturday, September 6 and Sunday, September 7 at The Stage at Suffolk Downs, 525 William F. McClellan Highway in Boston, MA :: 1 p.m., all ages, $75.18 to $257.86 :: Event info :: Advance tickets