Editor’s Note: This review originally ran as part of our coverage of the 2024 Toronto International Film Festival, and today we’re re-publishing it with the film’s wider release. Check out our extensive review slate of TIFF 2024, and revisit our official preview and complete archives of prior editions.

To get things started quickly, I’ll let you know that Mike Flanagan’s The Life of Chuck is the best feature film he’s directed since Gerald’s Game, and it might be an important milestone in his evolution as a filmmaker. But for me to adequately say why, I have to give a little bit of context to a statement I’ll make at the end of this paragraph. Should you read a plot synopsis after that sentence, you might think, “Hey, didn’t this guy just bitch about David Gordon Green making an overly sentimental and cliché-ridden cheese-fest?” And you’d be right; I did and stand by it. I don’t have a problem with sentiment — I have a problem with its application and purpose. In addition, there’s so much I normally hate in movies that are well-represented here – random-seeming dance breaks, maudlin heartstring-tugging, cozy catastrophes — but Flanagan makes them gel together into a coherent whole, adapting Stephen King’s short story into an emotional epic in which the totality of one’s life is evaluated, examined, and rendered in caustic yet poetic metaphor. What The Life of Chuck does differently than its peers is that it tempers its saccharine elements with a cutting bleakness, much like Frank Capra did.

Now, that great director is unfairly maligned for making “Capra-corn,” or overly idealistic and sentimental features that plug away at the heartstrings when – and this is important – stripped of their context. Take, for instance, It’s a Wonderful Life, a movie that is essentially remembered as being its third act: What follows before is essentially a suicide note, penned in vivid and miserable detail, in which we watch as George Bailey gets tossed about by petty cruelties inflicted upon him by fate and the ever-stormy tides of history. When watched outside of a tryptophan and eggnog-induced stupor, George’s moment in the sun, in which everything comes together for him after he’s been saved by Clarence the Angel, is an exception to the rule of his life – and tomorrow will likely be the same.

But we remember that film for that moment, much as he will, as a meager yet significant reward for his endurance, for the qualities that sustained him until his breaking point. Capra himself was bitter – having worked adjacent to the Signal Corps in World War II, he’d had his faith and mettle tested, though not to the same extent that, say, George Stevens or William Wyler did. To put it bluntly, Capra was angry and he was fucking depressed – qualities that are omnipresent in It’s a Wonderful Life. That movie ruined his career – being a box office failure that only earned its status as a Christmas movie due to its weird copyright purgatory after his new production company went under, airing as filler on local access stations during the holiday season. It was the end of his road, given that the HUAC had its sights set on his friends and that he was growing irrelevant. But he still made It’s a Wonderful Life, and that gorgeous film is more than its history.

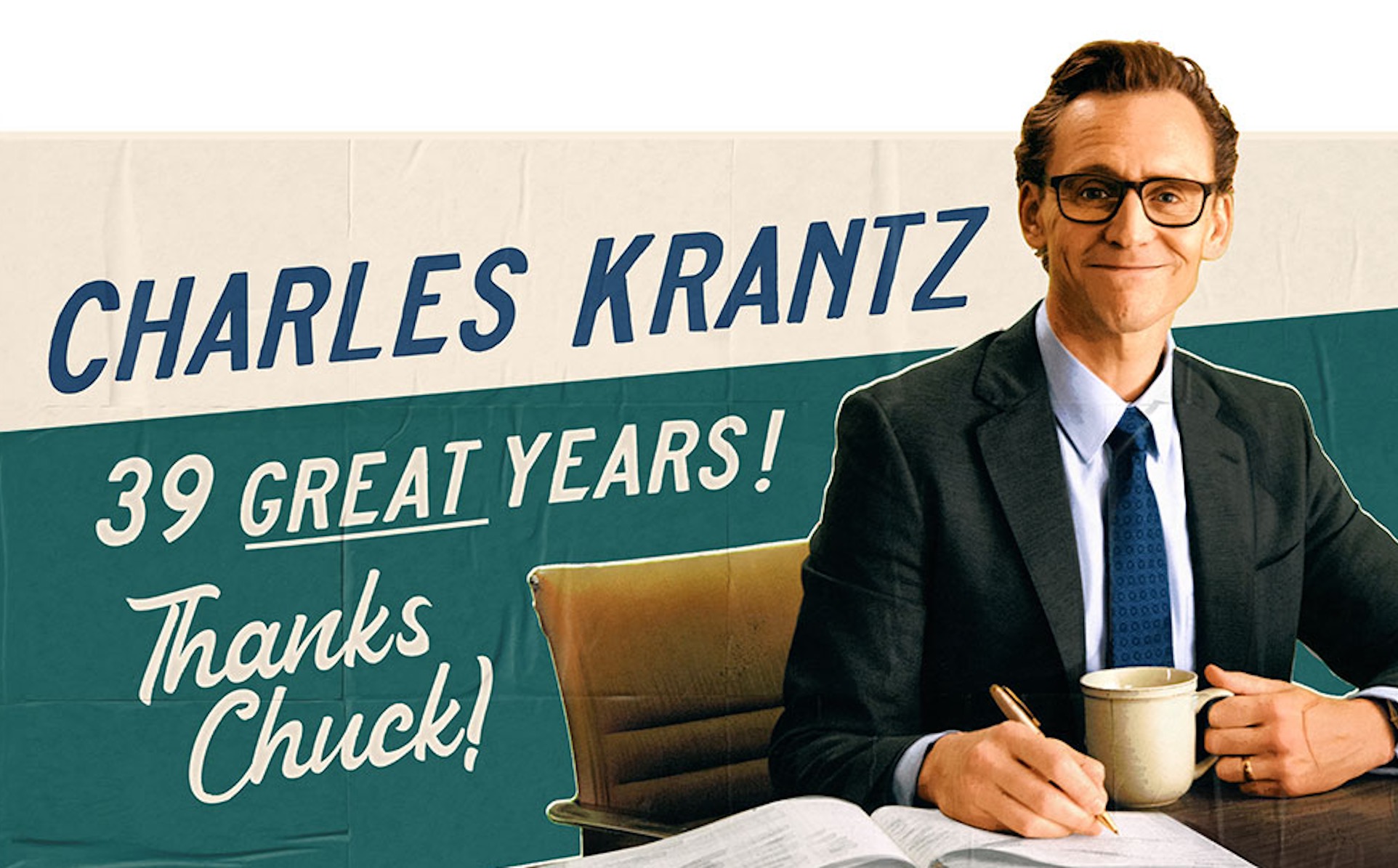

Flanagan and King take a similar tact here – we watch as Charles Krantz (Tom Hiddleston) leaves his mark on the world. At first, it’s somewhat of a mystery as to why: we wonder, alongside Marty (Chiwetel Ejiofor), a public school teacher who spends his days trying to keep his remaining pupils paying attention to Whitman recitations instead of the constant doom-filled news alerts that hit their phones, why he’s showing up on billboards all around a small town. They’re congratulating him for 39 great years – presumably, he’s retiring from something, though the billboards, TV commercials, banners, and bench signs never specify what precisely that is – though it is probably fitting that his career’s coming to an end, given that the world is. California is breaking off into the ocean, volcanos are erupting in Germany, and civil unrest is the name of the game in pretty much every other state – but the quiet town that Marty lives in doesn’t have the histrionics.

There’s nowhere to run, after all, or food to stockpile. There’s no point in surviving, as Marty’s ex-wife (Karen Gillen), one of the few remaining nurses at the town hospital, knows: she and her colleagues have dubbed themselves “the Suicide Squad,” given how their days are mainly spent patching up the maimed. But what does any of this have to do with Chuck? He only started appearing when things truly started going to hell, and his appearances are getting weirder: the television ads show his face slipping into a grimace from his pinched smile. The answer is revealed at the twenty-minute mark, and it is a devastating one.

But the movie continues for an additional hour and thirty minutes, as we get to know a little about the man who is ending this world and why. We watch him in a moment of glory as he stops, midway through a trip to an accounting conference, to dance to a busking drummer’s beat, in full flagrance, kicking out the jams Chris Walken-in-“Weapon of Choice” style. It’s a beautiful space of time, made all the more potent by what will later happen to him and everyone he knows. The last bit of the film is reserved for Chuck’s childhood, in which we learn about the tragedies that defined his upbringing and the love that saved him – that of a kindly grandmother (Mia Sara) and grandfather (Mark Hamill), who pass on a passion for dance and numbers to him. But lurking in the Victorian House they all live in is truly horrifying – something padlocked away in the house’s turret room that Chuck’s grandfather desperately wants him to avoid. That’s because he’s looked at it, the thing that lies behind that door, and he knows what horrors it can inflict on the mind. This, perhaps, is the key to the whole story: the thing behind the door holds all of the secrets.

Now, I’ll say that I’m not lying to you in writing that description, but you should not assume that this is a horror movie – I am trying my goddamnedest to prevent you from spoiling yourself, should you choose not to read King’s story. Perhaps a cosmic horror story would be a fair comparison, though the Lovecraftian Old Gods are absent here, aside from the one that awaits us all at the end of all things. But what Flanagan does better than most modern King adaptors is nail the author’s sensibility when it comes to heavy emotional expression – outside of the shock value and competence of Gerald’s Game, the best King moments that Flanagan put on film were the moments in which Danny demonstrates why he earned the nickname “Doctor Sleep.” He has an uncommon gentleness in dealing with messy sentiment, refusing, much like King does, to slip into histrionics during quiet moments. He lets the serenity and calm buffet the fear and sadness towards a devastating impact, a decidedly challenging feat to pull off even in the best situations for the greatest filmmakers.

King has lived long enough to write a story like this, endowed with the meaning only experience can adequately provide. His caustic reminders of the situation at the most joyous moments only give them a properly ephemeral beauty. This is why I can stand the fact that Hiddleston puts on the Ritz or that the movie devotes itself to explaining that specific moment at the risk of entirely alienating the hopped-up horror audience expecting one of Flanagan’s Netflix shows. It is just not that kind of film, so do not expect jump scares, ghouls, or whatever goes bump in the night.

You should expect, however, a well-meaning and genuinely moving exploration of the concept that “all we have is now,” to quote from when the Flaming Lips were still a good band. I think the reason I fully reject the kind of “cozy catastrophe” cinema is that it feels artistically stilted and banal, a repetition of the same old disaster narratives simply awash in detachment. It’s often good for still imagery, but it makes for a soulless cinema in which the characters accept what is happening to them without even so much as a hint of processing. They’re so thoroughly numbed to their reality that they can’t even register even an approximation of emotion, which is not a plea for every actor in one of those films to break free of the mold and start chewing the scenery, but rather just an ask that those who create these kinds of tones watch The Life of Chuck and see how Flanagan handles these topics in that opening act.

For example, David Dastmalchian shows up for a minute or two to talk with Ejiofor at a parent-teacher conference (yep, they’re still happening even during the apocalypse), which gets sidetracked into a discussion of how the internet is going down – including Pornhub. This is the thing that breaks him: his wife’s left him, his child is struggling with the loss of one of his parents, and the man is only able to see the cosmic cruelty of Pornhub being taken away at the start of what might be the end of everything. It’s a funny moment but a resonant one: as everything is going to hell, it’s the little indignities and details that give these kinds of things their psychological weight. A disrupted routine or a ripped-away creature comfort is just the first domino to collapse one’s sense of stability – one doesn’t simply shrug that off.

Does Flanagan approach treacle territory? Are we going to coin “Flanagan-corn” after this? Well, yes and no. The movie does veer towards those territories near the end, but Flanagan preserves King’s structure as a bitter reminder of the context informing it. But saccharine or not, all I really ask from these types of movies is that they earn the tears they wring from the audience, and The Life of Chuck earns every last drop it spills. Coming out of the Princess of Wales on Saturday night, I was surrounded by sniffling, mascara-smeared people who had been moved to a more outwardly apparent extent than I was. Yet I’m sure we were still thinking of similar things: Loved ones, either passed on or present, or the expanded surveys of what we were doing with our time on this planet.

This, too, is like It’s a Wonderful Life, which poses the same question to the audience that Clarence does to George Bailey – what would the world look like had they never existed? And would they like that world? Those butterflies are never quite what you’d expect – the alternate world from that “Sound of Thunder” would probably be a lesser place without you in it. Flanagan and King take a different tactic but present us with a similarly potent query. I’ll leave it up to you to find out what exactly its nature is, but I’ll say that you should find out for yourself as soon as you can see this. It’s truly top-tier work from all involved.